Reflections on work - from the past

I originally authored this post in April 2020 not too long after the COVID-19 pandemic caused cities and nations to lockdown. I found this as a draft post that I hadn’t published perhaps due to all that was going on at the time.

What I wrote here in April 2020, still holds in September 2023.

An image of a person standing on still water, which causes a reflection of the mountains and sky. Source: Unsplash

“If we cannot recognize the truth, then it cannot liberate us from untruth. To know the truth is to prepare for it; for it is not mainly reflection and theory. Truth is divine action entering our lives and creating the human action of liberation.”

Reflections on work

I've worked as a 'digital education facilitator / senior teaching associate' for almost 3.5 years at the Lancaster University Management School. I arrived hopeful, looking ahead to entering a new phase of my career within higher education where I would be explicitly working with a range of colleagues - academics, administrators, subject librarians and students - to develop both blended and online learning experiences. My time in my current role is coming to an end as I plan to move on to a new challenge and to both undertake a doctorate. In many ways, it makes sense to do these in the same place. In this post, I share some thoughts, reflections and hopes.

Synergy is key, when enacted

My current role is based in a large management school - a business school - where you have a range of business subjects divided into departments ranging from Accounting and Finance; Economics; Organization, Work and Technology; Management Science; and Marketing. There is also the Undergraduate Office where consortial programmes are situated.

One of the best part of working in such a large school was getting to meet a range of people from all walks of life and experiences. There are a lot of colleagues who care about their students. Indeed, the Dean at the time of this writing has had a project that sought to develop a cross-departmental community for students which takes the form of a module called MNGT160: Future Global Leaders: Sustainability Across Business.

This module has often been a source of contention as it sought to create a community that cuts across departmental boundaries, and thus, requires both contribution from each department and some hours to be workloaded from each department. Since it is not 'owned' by any one department, this module has, at times, not received a welcoming view. However, the aim and ethos of the module are fairly sound: to create a community while developing some graduate attributes within students through getting them to work together across their subject silos. Idealistic? Perhaps. Doable? Definitely.

With the amount of expertise and experience across the management school, such a module has great potential to create a very collaborative, cross-departmental community of learning and teaching that could strengthen the identity of the school itself while creating networks of students (and staff) who could work closely together in order to grow, develop as students, people and future professionals and subject experts.

Synergy is key for such a module to happen. Working together and drawing upon the expertise of such a large school to create good curricula, well-structured systems and a positive, welcoming environment for learning can only be a good thing surely.

The pandemic and the move to digital

Covid19 has upended a lot of systems, processes and practices. Initially, there was a lot of uncertainty that allowed some leaders to emerge in order to mitigate some for the panic and anxiety that the sudden shift or pivot to digital education that the pandemic caused.

During these first weeks and months, a lot of educational technologists were doing their utmost to help staff however and wherever possible. In fact, this is still continuing. What has been at the back of our minds - some of us - has been those little fleeting thoughts of ah, if we only had more blended learning before, we'd be more prepared for this!

Of course, learning/educational technologists have been trying for years to get academic and teaching staff to integrate in the digital into learning and teaching. We do this because we understand that, on the whole, students require a full range of digital literacies in order to live and work within the 21st Century to the full. People can live without collaborative and smart technologies, sure, but the world is generally progressing in the direction of closer collaboration and working together through digital means. Sustainability, efficiency and richness of opportunities are just a few reasons that digital literacies and their development are so key for the future. We could not have predicted the pandemic, nor used this as part of a rationale for integrating digital education practices for sounding, at best, alarmist.

That all said, what the pandemic has caused for digital education is a few points:

a sudden, renewed interest in digital education, whether blended or fully online;

a deeper understanding of working and studying at home, and how this can work;

a better appreciation for educational technologists and those who have integrated digital education practices into their teaching;

the development of a range of solutions to address issues arising around learning and teaching both remotely and at a distance;

and many others.

The fourth point is particularly interesting for me within my current role because I have been able to observe developments locally, nationally and internationally through a mixture of professional networks sustained by email lists, social networks on Microsoft Teams and Facebook and looser networks on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Working in silos: missed opportunities

Initially, I observed the same questions arising from the different places. I frequently saw the same or very similar questions coming from a range of staff that mostly where 'how to?' questions. I helped wherever I could by providing advice, solution and consultations where appropriate.

I began observing with a bit of annoyance and sense of powerlessness a pattern that slowly began to develop: colleagues were working in their departmental silos to create solutions. These solutions were not always shared across the departments at a macro level. As far as I was concerned, given my role and position that allowed somewhat of an overseeing eye, if I did not hear about it, I believed that a potentially valuable idea was not being shared to colleagues whom might need or find value in such solutions.

To my mind, this type of working did not make sense for a few reasons:

the problems themselves are common across the faculties - the 'how to?' questions;

solutions/ideas created in silos and thus not shared is, in effect, a replication of effort;

those with the most experience within digital education were not always consulted first despite their expertise, and in effect, time and attention was misused;

Generative AI: a problematic illustration of the intersections of racialized gender, race, ethnicity

NB: this post is a draft and subject to change; it forms a pre-print (an author’s original manuscript) I have authored.

Learning, teaching and technology have often been a big part of my career - since way back to the mid/late-2000s! Now in 2023, talk of artificial intelligence and education is omnipresent, and it's here to stay. Machine learning allows AI tools to become more intelligent by drawing on datasets to develop expertise over time. However, AI tools rely upon raw data created by humans; these datasets, in turn, reflect the biases of those who have gathered the evidence, which will be racial, economic and gendered in nature (Benjamin, 2019, p. 59).

Several researchers (Noble, 2018; Benjamin, 2019; Mohamed et al., 2020; Zembylas, 2023) are looking into the underpinning reasons that enable AI to skew results and create representations that overlook and erase others while focusing on specific, dominant groups. Specifically, the way that the human-created algorithms informing AI and generative AI tools portray racialized, gendered people is especially problematic. To understand why problematic representations of people are created, it is worth looking at the ideas of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991; hooks, b, 2015; Hill Collins, 2019). I draw on bell hooks and Patricia Hill Collins’s works here and recommend the reader acquaint themselves with Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work.

I write this post from my position as a part-time doctoral student, educator and higher education worker at a Scottish university in the UK. I write it as someone who’s interested in and curious about technology and as someone who teaches, develops, coaches. mentors educators (lecturers) how to teach and augment their teaching practices. However, I also write it from the perspective of a US migrant and dual national who has lived/worked in China, Russia, Kazakhstan and the UK. I note these as they inform my positionality when writing this post as I am interested in the interplay of education, culture, media representation, critical pedagogy and decolonial thinking as some of the ideas underpinning these areas inform some of my personal and professional values.

As a colleague of mine wrote "As per the Russell Group principles, I strongly believe it’s my job as an individual educator and our job as a sector to guide students how to use AI appropriately." I take their words and apply them to my own context: I believe it is my job as an educator to guide students and university staff in understanding and using AI appropriately.

For educators, this will give you an insight into some of the affordances of generative AI tools for creating images while exposing you to some of the opportunities and serious problems of using, for example, DALL-E, to create images. This post should give you ideas for developing your own practice with your students and your colleagues, no matter their experience as educators.

Thank you to colleagues and friends who have helped expand my thinking when writing this post.

Introduction

Using generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools can be exciting, confounding, scary and confusing. This was my experience and observation upon showing an academic colleague how a generative AI tool like ChatGPT can work by taking text prompts that are then create text-based content. Although text content creation tools have been at the forefront of everyone's mind since at least mid-2022, there are other generative AI tools that exist and merit attention. At the time of this writing, I can see common generative AI tools being categorized into three or four major types:

text to text (e.g. ChatGPT, Google Bard, Cohere.ai)

text to image (e.g. DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion)

text to media, such as audio or video

and text-to-code, for coding and programming purposes

In this post, I focus on text-to-image generative AI through example prompts that I created. I analyze what it produced to demonstrate that educators must experiment with generative AI tools to understand and critique the tools and what they produce. In doing so, we can begin to understand how and why such tools create the content that they do. I use intersectionality as a heuristic (Hill Collins, 2019) to analyze the AI-generated avatars by looking at how these represent socially constructed identities in terms of racialized gender, race, ethnicity and nationality. Humans create algorithms and algorithms, in turn, create representations based upon human-created algorithms.

Specifically, we can deepen our understanding the reasons that generative AI tools (and other technologies) create questionable content that might, at the very least, underpinned by stereotypes representing an intersection of racism, misogyny, classism and/or xenophobia.

Finally, we must recognize that, for the moment, there is no concrete solution that a lay academic or layperson can implement to achieve this without a collective, concerted effort that includes a range of groups focused on shining light on the issues, changing hearts, minds and code and imaging ways forward to an equitable, inclusive world. Decolonial thinking can offer some imaginations to counter the coloniality of AI.

I first provide the context by laying out four (4) example prompts that I created an entered into DALL-E. I briefly touch on the prompts I created before moving on to analyze the results of each of the prompts. I provide a basic critique of the subsequently created representations by looking at the atmosphere, decor, clothing, facial expressions, ethnicity, or race.

For clarity, I use definitions of race and ethnicity offered by Fitzgerald (2020, p. 12) that sees race as referring to a ‘group of people that share some socially defined characteristics, for instance, skin color, hair texture, or facial features’ while ethnicity encompasses the ‘culture, nationality, ancestry and/or language’ shared by a group of people irrespective of their physical appearance (ibid). Grosfoguel offers another take on race informed by decolonial thinking: race is what he terms ‘a dividing line that cuts across multiple power relations such as class, sexual and gender at a global scale (2016, p. 11). In this case, race and subsequent racism are institutional and structural in nature in that the concept of race creates hierarchies of power and domination which are compounded by gender, sex, class and other factors.

While the concepts of race and ethnicity are social constructs and neither are mutually exclusive, I use these definitions to frame my analysis.

I highlight what is represented, and why the representations might appear this way and leave you, the reader, with critical questions to consider as you and your prospective students/learners explore the usage of generative AI for creating images from text. I then offer some possible solutions drawing on decolonial thinking.

NB: some readers will find the results disturbing, upsetting and potentially angering.

Sweet old grannies

Generative AI allows us to experiment with ideas to then create representations of those ideas, whether these are text, images or other media. In these short cases, I asked DALL-E to create illustrations of sweet old grannies making pancakes. As a reminder, DALL-E is one of three major text-to-image generative AI tools, and there are many others out there.

This was an impromptu idea that came up for a few reasons. In my current role, there is much discussion on the issues of generative AI and how to prepare students and educators. I also like pancakes and I have some fond memories of one of my grandmothers who would visit regularly when I was younger. I also worked and lived in Russia for a while where both pancakes and grandmothers are a big part of the culture. Pancakes are big around Maslenitsa or Carnival as it is known in other countries that celebrate the Western Christian version of the event, while grandmothers are a major cultural symbol, source of unpaid family work (Utrata, 2008) and symbol of stoicism that represents an intersection of age, gender and class (Shadrina, 2022). I also thought it would be playful and also allow me to see how DALL-E, a tool created by humans who programmed algorithms, would represent humans.

For transparency, I acknowledge that I am using gendered, ageist and even stereotypical language, especially in terms of describing 'a sweet, old X grandmother'. I am also aware that I am focused on a particular type of social/familial role, a grandmother. Not all old(er) women are grandmothers and not all grandmothers are old! As Benjamin (2019, pp. 102 drawing on Blay, 2011) asserts, qualifying words - those adjectival words used to describe 'opinion, size, age, shape, colour, origin, material, purpose' (Dowling, 2016) often encode gender; race, racism and racialization; and the humanity of individuals and groups of individuals (see Wynter, 2003).

Initial prompts

I used a prompt and only changed the adjectival qualifier describing the national origin of the imaginary character or avatar: "Create an image of a sweet, old X grandmother making pancakes". I tried out these prompts over a period of two weeks in July 2023. The queries I created are these:

"Create an image of a sweet, old Polish grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old Russian grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old American grandmother making pancakes"

"Create an image of a sweet, old Black American grandmother making pancakes"

I use specific terms to get the generative AI tool DALL-E to generate specific results to allow me to see what the AI tool produces so that I can then analyze the results. This, in turn, offers evidence and clues to understanding how human-created algorithms create the outputs that they do within generative AI tools.

In each case, DALL-E created four (4) individual representations of each character or avatar to illustrate the prompt I had created; in total, there are 16 images which you can see below with a caveat. Generative AI does not currently do well with the finer details of humans such as facial expressions, eyes, and hands. While I won't focus on hands and eyes specifically, facial expressions and ethnicity will be important later.

Representations of Polish and Russian grandmothers

At first glance, to the untrained eye and perhaps even to the untravelled eye, we might think nothing is amiss. There are four different images created that seemingly portray what is meant to be a sweet old Polish grandmother who is making pancakes, and another four representing Russian counterparts. Generative AI does not currently do well with the finer details of humans such as facial expressions, eyes, and hands. While I won't focus on hands and eyes specifically, facial expressions will be important later.

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

As we can see, each image illustrates a sweet, old Polish grandmother who appears to be in an almost gloomy environment. The lighting isn't bright but rather dark and almost shadowy. The representations of their Russian counterparts are very similar in many ways: the atmosphere is dark, perhaps gloomy. We can see what looks like wooden utensils being used and in some of the windows, we can see stereotypical lattice-type window net curtains.

Such portrayals could indicate a lack of modern lighting and/or electricity. The light also indicates the time of day, which could be an early morning golden hour, when they might rise to make an early morning breakfast. This does offer a stereotyped, ageist view of the women represented, however, by generalizing that all might rise at a very early hour to make pancakes.

If we look at the clothing, we see that each avatar is wearing clothing that is stereotypical of elderly Polish and Russian women: patterns that are floral in nature while headscarves. Some women do occasionally wear headscarves when attending church. However, these women are depicted in the home. However, we don't really get any indication of their hair or hairstyles, or whether these are things they might worry about simply because the representations cover or hide this particular aspect of all of these women.

In each case, it seems that perhaps these avatar-grandmothers are living in a different time based on the depictions of the atmosphere and technologies they are using. This doesn't mean that some do not live this way, however, it is problematic as certainly not all might live this way depending upon their means, wealth and family ties.

Expressions and ethnicity

The expressions of the Polish and Russian grandmothers are problematic for a few reasons. If we look at each of the women, most of them appear to be looking either down or away with only one of each looking ahead at the imaginary camera. The images as a collective might be seen to represent a sort of melancholic and depressing environment.

The women are either expressionless or perhaps seemingly unhappy in the eyes of someone from the US or UK apart from one of the Polish avatars. While there may be socio-historic rationales for portraying the women in such a way (e.g., World War I and World War II, followed by the Cold War) these images are explicitly problematic as they represent stereotyped, gendered and xenophobic representations of elderly Polish and Russian women.

In terms of ethnicity, for both the images representing these groups, all of the women are White or appear to be White. Poland, according to some statistics is 98% Polish so perhaps the representations are close to portraying the norm. On the other hand, Russia is more complex with its 193 ethnic groups yet the images portray a high level of homogeneity.

Ethnic Russians make up 77-81% of Russia's population of 147 million, along with Tatars, Ukrainians, Baskhirs, Chuvashs, Chechens and Armenians being other major ethnic groups of over a million (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Russia#Ethnic_groups and https://minorityrights.org/country/russian-federation/ for a breakdown; there are other Russian-language sites that you can check as well). My point is here that Russia is a diverse nation of peoples of ethnic backgrounds and mixes including those of Slavic, Turkic, Caucasian, Mongolian peoples, indigenous and Korean ancestry. However, the images created by DALL-E portray avatars that represent only those who appear Slavic and/or European (i.e. White). There are no representations of other types of Russians who may be Turkic, indigenous, or Mongolian in origin.

However, this could be due to how algorithms encode the concept of a Russian person. Does 'Russian' mean a citizen of Russia, and therefore anyone who lives in Russia? If this is the case, then it is likely dominant views that inform datasets will skew any possible representations. On the other hand, does it mean those that see themselves as ethnically Russian? If this is the case, then perhaps it is valid to show only Slavic/European avatars. In either case, the representations are problematic as they highlight whatever the dominant 'norm' is while erasing Russia's historically rich diversity. Another perspective could be how a particular government might influence how the imaginations of its populace are portrayed, which may mean the prominence of a dominant group at the expense of an ethnic minority group. In Russia’s case, there are concerns surrounding ethnic separatism and how migrants are portrayed, especially of those from regions traditionally associated with Turkic and Asiatic peoples and those whose faith is Islam (Coalson, 2023). However, such concerns are not reasons for erasing different representations and portrayals of peoples of different ethnicities.

Representations of grandmothers from the US

As a reminder, I used the following prompt: "Create an image of a sweet, old American grandmother making pancakes". I acknowledge that using ‘American’ can be problematic. It can refer to people of the United States, or if you live in Latin America, American can refer to anyone from the Americas, not just people who live in the United States of America.

In addition to the term ‘American’ being problematic, this prompt quickly revealed more serious issues that I will touch upon.

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

The images of American grandmothers offer a stark contrast in many ways when compared with the representation of Polish and Russian grandmothers. The DALL-E produced illustrations appear to show these women, for the most part, in a different light.

While the first two women in the top row appear to be in the home, their homes appear to be more modern in some respects. They all appear to be using what appear to be metallic utensils as opposed to wooden ones. The lighting in the bottom two images is much brighter with almost an appearance of a representation of a cooking show as indicated by the lighter-colored walls. The atmosphere appears a lot less cluttered and lighter in many respects. This lack of clutter and more light might indicate, at the very least, modern homes that are efficient.

Then there are the hairstyles. These are, admittedly, something that I hadn't picked up on as it wasn't something that I am fully literate about until a friend prompted me. As that friend noted, the hair of these women tells another side of the story related to class. What does the hair say to you? How do each of their hairstyles represent their own lives? What does each style say about their socio-economic background?

The clothing also offers clues to how these avatar-representations live. Their clothes appear more modern, perhaps more expensive than their Polish and Russian counterparts. What does this say about the data that has informed the creation of these avatars?

Expressions and race

If we look at the facial expressions, again while generative AI does not yet get the finer details right, something appears and feels more warm, perhaps more positive about the expressions of these avatar women. The first one appears thoughtful and focused on what she is doing with almost a sense of enjoyment. The second one appears content - at the very least - with what she is doing. The third and fourth images appear to represent a wholly positive image of two different women engaging in cooking as indicated by slight smiles whether looking down (image 3) or looking straight ahead (image 4).

However, there is a significant problem with these representations which is indicated by the perceived race of the sweet, old, American grandmothers: each avatar represents a White woman. This is particularly problematic as the US has a population of over 330 million with nearly 80 million (nearly 1 in 4 people) who comprise non-White people. The question here then is why has the generative AI tool created only White faces to represent the qualifier ‘American’ when 1 in 4 people in the US fall under the broad categories of Black, Asian, Indigenous and others? Why is the US portrayed as, at least according to these AI-generated images, representing only one part of its population?

Representations of grandmothers from the US racialized as Black

Atmosphere, decor, clothing

If we consider the representations generated by DALL-E below, we see deeply problematic underlying issues that represent an intersection of race, gender and class in the portrayals of imagined sweet, old Black American women.

The atmosphere in each avatar appears generally warm and inviting, reflecting the representations of sweet, old, ‘American’ grandmothers. There is a certain simplicity and modernness to the environment. Two avatars appear in a home kitchen (the bottom two) as indicated by kitchen cabinets/cupboards and a nearby window. The top-left image appears perhaps in a larger, commercial kitchen or perhaps a kitchen in the home, and the second (top-right) appears perhaps in a TV studio as indicated by the lighting and focus.

One colleague, Dr Ruby Zelzer, notes something that I had missed:

… something struck me about how utilitarian the kitchens were, the kitchen tiles in 3 of the 4 pictures, and also that the type of tiles were very basic in appearance. How none of the other images had these tiles (to my eye).

However, the images appear to say something about the roles of these avatar women. Three of the images appear to represent the avatars as cooks or chefs, as indicated by what appear to be chefs' hats and their attire in general. The avatar in a pink apron and white outfit (top-right) appears to be in an ambiguous situation in part due to the lighting and the red nose: are they in a TV studio or in a circus? I will discuss this later as the representation harks back to minstrelsy and blackface.

In addition, two of the avatar women are wearing what look like cleaner gloves. The avatar portraying yellow gloves is also problematic as the gloves appear slightly worn and tattered. This can be seen to place someone, or here an older Black American woman, in a lower socio-economic position.

In 3 out of the 4 images (all bar the lower-left image), the avatars representing Black American grandmothers are situated in positions of service through the attire that they are portrayed to be wearing. In fact, only the avatar in a blue shirt and pink apron appears to be in a position that seemingly isn’t attributable to a service role. In contrast, the White representations of American women don’t appear to be in positions of service as indicated by their clothing. I now turn to discuss the problems that nearly all of these images is (re)producing.

Expressions and race

All the women appear to be smiling or enjoying what they are doing. At first, this may seem like a good thing. However, the expressions of the top-left and bottom-right avatars are highly problematic for a few historic reasons rooted in racist, gendered and classist portrayals of Black American women. In addition, the larger bodies of three of the other avatars also reflect how Black American women have historically been portrayed within the United States and beyond. In contrast, the avatars representing White American women are constructed with what appear to be more delicate and smaller features, something that several researchers (Bowdre, 2006; Downing, 2007; Thompson Moore, 2021) argue has frequently been attributed to representations of White women.

The origins of stereotyped representations of Black American women lie, in part, in minstrelsy in the 1800s (Bowdre, 2006; Downing, 2007; Thompson Moore, 2021). In minstrel shows, White men portrayed Black Americans by blackening their faces using burnt cork while exaggerating other facial features, such as the lips, by using 'red or white paint' (Bowdre, 2006, p. 37). The avatars representing Black American women are illustrative of how Black women were constructed in minstrel shows through the caricature of the wench (Thompson Moore, 2021, p. 318). White men performed the wench character representing Black women through cross-dressing and drag performances (ibid). Other characters would go further by dressing in 'brighter, more flamboyant dress' and their faces would be further exaggerated by makeup, creating 'larger eyes and gaping mouths with huge lips' (ibid). As Bowdre (2006) asserts, minstrelsy has aided stereotypes around people racialized as Black and continues to inform media representations of Black American men and women in the present day.

Another representation is that of Black American women as a ‘mammy,’ or a good-natured, submissive and motherly figure who would provide care for White families. Taken together, an excerpt from King (2019, p. 13) explains why such representations are deeply problematic:

“Aunt Jemima,” a well-known trope that (mis)represents/distorts Black/African womanhood in the USA, is a fictional historic advertising icon that reinforces the national stereotype of the slave plantation “mammy.” In the late 19th century, this image of a smiling, usually corpulent dark-skinned Black woman wearing a red bandana became the trademark logo for a technological innovation: ready-mixed pancake flour. Commercial advertisements that invented this denigrating image of Black womanhood expressed the white imagination, which was then reified in film, fiction, the fantasy world of plantation mythology, and consumer consciousness. This stereotype epitomises the dominance of hegemonic white memory and imagination in the material culture of American society (Wallace-Sanders 2008).

The images below depict what hooks (2015, pp. 65-66) would argue that such images portray Black women in a negative light through the construction of Black women having ‘excessive make-up,’ ‘wearing wigs and clothes that give the appearance of being overweight’ while simultaneously representing large ‘maternal figures’. bell hooks's message here is that historical depictions of Black American women portray them as fat/obese, older, asexual and unkempt, homogenizing this group while mocking them through the ‘wench’ and/or ‘mammy’ stereotypes, which both (re)produce demeaning representations of Black American women.

Discussion

What we see here in each of the images represents what are what Benjamin describes as (2019, p. 59) ‘deeply ingrained cultural prejudices’ and ‘biases’ drawn from data that the generative AI tools use to create representations.

While the imaginary representation of Black American women was reified in media and consumer consciousness, we can see that this portrayal resurfaces in the digital realm within the context of generative AI. What we see here then is one manifestation of ‘algorithmic coloniality’ (Mohamed et al., 2020; Zembylas, 2023). For those new to the concept of coloniality, this is a state of knowing and being that pervades knowledge and power relations that sees those formerly colonized and/or enslaved as regularly encountering inherent disadvantages in all aspects of life while former colonizers retain many advantages in all areas of life (Quijano and Ennis, 2000; Wynter, 2003; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015). In simple terms, this means that accepted knowledges and ways of being represent those of the dominant members of society.

In this case, the role of Silicon Valley, located in the United States, which is a hegemonic power and an extension of the former European colonial nations as one of her settler-colonies, is significant. This extends beyond the technological companies of Silicon Valley and elsewhere in the US to anywhere that readily accepts, uses and replicates their models. Those who follow the dominant modes of cultural, and technological production take part in the creation and perpetuation of algorithms which overvalue some humans (those racialized as White) while undervaluing and actively devaluing the humanity of other humans (those racialized as Black, Asian and others).

Considering the #BlackLivesMatter movement and the daily injustices that people racialized as Black in the US (and elsewhere, even the UK for example) experience, it is particularly problematic that human-authored algorithms informing generative AI reflect dominant systems of knowing and being. It is, however, a testament to the existence of coloniality within AI and AI algorithms which (re)produce gendered, racist and xenophobic representations of racialized and minoritized peoples.

Although there is some hope for everyone to influence the datasets that inform algorithms, which in turn might allow for some change, this will not be easy: collaboration will be key and conscientization of everyone on the issues will be as well to address and rectify the issues of problematic algorithms, which are just one tool in a greater system.

Some specific solutions can help by drawing on decolonial thinking that can develop and deepen the understanding of students and educators. This can start with understanding where sites of coloniality replicate harmful generative AI algorithms. Drawing on Mohamed et al. (2020, p. 8)this might include understanding and identifying such sites, which might include where and how algorithms are made and function, who is involved in beta-testing and testing generally, and what local and national policies can be developed. This also includes specifically developing algorithmic literacy as part of digital literacy initiatives (Zembylas, 2023)

Key questions for students/educators

Why do the avatars represent these particular groups in the way that they do?

What, if anything, do the representations get right?

What, if anything, do the illustrations get wrong?

How are the representations problematic?

Where representations are problematic...

What message does this send to someone without knowledge of the context?

What message does this create about the people/cultures/objects portrayed in the images?

What can you do to ensure generative AI creates, if it is possible, more accurate and equitable representations of peoples/cultures/objects?

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press.

Bowdre, K. M. (2006). Racial mythologies: African American female images and *representation from minstrelsy to the studio era. [Doctoral dissertation/thesis, University of Southern California].

Coalson, R. (2023). Russia’s 2021 Census Results Raise Red Flags Among Experts And Ethnic-Minority Activists – RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2023-07-24 from https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-census-ethnic-minorities-undercounted/32256506.html

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43, No. 6, 1241-1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Dowling, T. (2016, Tuesday, 13 September). Order force: the old grammar rule we all obey without realising – The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-07-24 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/13/sentence-order-adjectives-rule-elements-of-eloquence-dictionary

Downing, C. (2007). “Interlocking oppressions of sisterhood: (re) presenting the black woman in nineteenth century blackface minstrelsy”. Senior Scholar Papers, Paper 539. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/539

Fitzgerald, K. J. (2020). Recognizing Race and Ethnicity: Power, Privilege and Inequality (Third ed.). Routledge.

Grosfoguel, R. (2016). What is Racism. Journal of World-Systems Research, 22(1), 9-15. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2016.609

Hill Collins, P. (2019). Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Duke University Press.

hooks, b. (2015). Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Routledge.

King, J. E. (2019). Staying Human: Forty Years of Black Studies Practical-Critical Activity in the Spirit of (Aunt) Jemima. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies - Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity, 14(2), 9-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2019.1690399

Mohamed, S., Png, M.-T., & Isaac, W. (2020). Decolonial AI: Decolonial Theory as Sociotechnical Foresight in Artificial Intelligence. Philosophy & Technology, 33(4), 659-684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00405-8

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality as the Future of Africa. History Compass, 13(10), 485-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12264

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press.

Quijano, A., & Ennis, M. (2000). Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533-580.

Shadrina, A. (2022). Enacting the babushka: older Russian women ‘doing’ age, gender and class by accepting the role of a stoic carer. Ageing and Society, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x2200037x

Thompson Moore, K. (2021). The Wench: Black Women in the Antebellum Minstrel Show and Popular Culture. The Journal of American Culture, 44(4), 318-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacc.13299

Utrata, J. (2008). Babushki as Surrogate Wives: How Single Mothers and Grandmothers Negotiate the Division of Labor in Russia. UC Berkeley: Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3b18d2p8

Wallace-Sanders, K. (2008). Mammy: A century of race, gender, and southern memory. University of Michigan Press.

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257-337. https://doi.org/10.2307/41949874

Zembylas, M. (2023). A decolonial approach to AI in higher education teaching and learning: strategies for undoing the ethics of digital neocolonialism. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.2010094

A great piece of research on mental health amongst English language teaching professionals

I recently participated in a study on mental health among English language teaching professionals. The findings have recently been released and I highly recommend that colleagues read the study and its results.Managers within ELT and EAP (English for academic purposes) might benefit from reading the results of the study. Mental health is a serious issue meriting consideration, especially within the worlds of ELT/EAP/TESOL which are often highly money-driven and fertile grounds for mental health issues and problems.One issue that I am particularly interested in is bullying and harassment within the workplace within Higher Education. These two issues are common causes of mental health issues within HE. From my experiences in HE, all of the worst managers I have worked with have been either clueless or purposefully malevolent in fostering a negative atmosphere by engaging in bullying and/or harassing behavior. On balance, all of the best managers and leaders I have worked with in HE have been keenly aware of these issues, the need to address them and the sensitivity and awareness of how to engage with staff who have or suffer mental health issues. So, there is hope!via The Mental Health of English Language Teachers: Research Findings

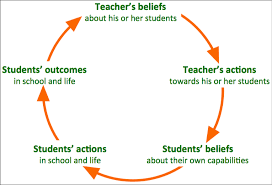

Thoughts on 'Why Believing in Your Students Matters' by Katie Martin

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

Today I came across this succinct article by Katie Martin on why believing in our students matters, as this can have a significant impact upon a teacher's practices and students' uptake of learning regardless of where learning and teaching that takes place - whether face-to-face or online.While I have known about the need to wait for responses from students for some time, and I value this approach, sometimes one can wait a bit too long. UK universities have had high and growing numbers of students from China for a while now. Some universities throw their doors open to International students since they pay higher fees.One such university near London where one Master's program of 150+ students has well over 95% of its students from China. At the same time, some of these same universities that seek to recruit large numbers of International students, often heavily reliant upon specific markets such as China, can, at times, lower the bar in terms of language requirements. From my own experience of observing and delivering teaching, this situation, which isn't unique to the aforementioned university, creates a number of issues since the students often:

- come with different levels of language readiness for an intensive postgraduate level of study;

- are not or may not be used to interacting and socializing with those from other countries;

- are unlikely to work outside their 'peer' group of compatriots due to shyness, peer pressure or do so begrudgingly; and/or

- lack confidence in their own abilities and are perhaps not provided with enough motivation from teaching staff to instill a positive, 'can-do' attitude to learning.

The result of any or a combination of these is that lecturers, academic tutors, learning developers and tutors of English for academic purposes are frequently put into tricky situations: the content has to be delivered, but if students are struggling to understand, what is to be done? Too often I have heard over the years, from staff at various institutions, similar negative remarks that Katie mentions in her article. I've always found these types of comments particularly demotivating and, silently, I ask myself upon hearing sustained negative comments "Well, why the hell are you in teaching?!" It is as if those making such comments were perfect students who always worked hard.On the flip side, the best colleagues I've had have always been positive, supportive and empathetic to the student journey. This empathy seems to set apart the negativity of the moaners from the teachers/lecturers whose lessons that we would always look forward to when we were once students. I think part of this empathy that some educators have is at least partially informed by the works of the Brazilian educationalist Paolo Freire, among others.Going back to Katie's article, I think one solution is creating a positive, welcoming environment that seeks to recognize the students as intelligent participants who are able to interact at Master's level successfully with regular, positive support that seeks to push the students' boundaries and to modify our teaching practices to engage the students in such a way that might tease out from them meaningful participation.One way, I believe, is to have a meaningful, welcoming induction to a program that gets students involved in getting to know their peers and teaching staff beyond the polite formalities of titles and names (think: basic teambuilding activities that get students to solve real problems related to their studies and/or life within their new educational setting). Oftentimes, I've seen inductions that were so superficially boring, stereotypical and/or dry that it immediately set the wrong (superficial) tone for the program of study in question.Another solution is to embed positive thinking throughout a program. As Katie says in her post:

... when we believe we can learn and improve through hard work and effort we can create the conditions and experiences that lead to increased achievement and improved outcomes.

In terms of learning and teaching, this is particularly powerful for our students. If they feel the above, they can and will improve in their learning journey. We, as educators, have a responsibility to instill these ideas into our students, especially International students who might genuinely need extra support, encouragement and motivation in order for them to become independent learners. Part of ensuring the success of our learners is to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students.This also means we might need to change our approach to learning and teaching. So, for example, imagine you have a session of 15-50 students and they don't volunteer answers without being called on and prefer to stare at their phone or laptops (or both!). If our students are quiet and reticent to raise their hands to volunteer an answer, then there are some easily-doable solutions.

- Creating regularly-spaced questions to gauge/engage/formatively assess learning can significantly help improve participation, and these can be easily delivered via a response system such as Mentimeter or similar as students only need to use their mobile phone/phablet/tablet/laptop.

- Implementing a Twitter feed so that students can engage during/after a teaching session can also foster learning by using a module/course specific hashtag. These two blog posts have a range of good ideas:

Apart from those small solutions, I believe that part of ensuring the success of our learners is also to change our thinking - to think more positively, and to believe in our students. So, for example, rather than immediately assuming that most, if not all, International students are likely to plagiarize essays, we can set the stage from the start by building a positive, supportive environment that seeks to educate rather than pontificate. Another quote from Katie's article below underscores my message:

“When we expect certain behaviors of others, we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behavior more likely to occur. (Rosenthal and Babad, 1985)”

Let's take plagiarism. I've often heard from colleagues both genuine concerns and negative comments/expectations of students in terms of plagiarism. This, in turn, leads to plagiarism being approached in an almost compelling manner within course materials: plagiarism is bad, and therefore if you plagiarize you are bad and so if you plagiarize, you will fail, etc.Using the above example, one relatively simple way to embed a positive approach to learning and teaching is to change the negative, hellfire-and-damnation discourse on plagiarism often present within course materials to one that offers an open, frank discussion on attribution and giving credit. One such way I have done this is by getting students to look up and understand attribution through discussion, and then following this up by reading an in-depth report on a politician who plagiarized a paper for a Master's degree. From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others).From what I have observed, these combined approaches give students a chance to explore the issue of plagiarism through a more empowering lens while exercising their academic literacies (digital and information among others). It gets them thinking and talking amongst each other rather than being spoken [down] to in terms of the issues of plagiarism. Along with the teacher creating an empathic, positive atmosphere, this also makes students feel part of the discussion and (more) part of the academic community as they seek to understand expectations that may be new and/or alien to previous educational experiences.Ultimately, the choice lies with the teacher in question to change their practices or not. There is always an element of risk to transforming teaching practices. However, without taking risks (even small ones) to innovate, one will simply never know how effective the changes to might be. Mulling ideas over is a good way to get started, but as with anything, mulling ideas over for an extremely long amount of time can kill ideas and innovation. Staff who have ideas should be allowed to experiment, and line managers should be proactive in supporting staff who are enthustic about learning and teaching.If things don't entirely work as planned or expected, well, at least learning has occurred on the part of both the learners and the teacher(s) in question. The light bulb and radio weren't perfected within a day's time, so why should a new teaching approach be perfected before trying it out?! Just do it!Just do it!

Ideas on teaching: should we abandon adherence to lesson aims?

Reflections on an article on Bakhtin & digital scholarship

I've recently read an article from the Journal of Applied Social Theory called 'Bakhtin, digital scholarship and new publishing practices as carnival' which discusses how digital scholarship causes disruption to traditional academic practices (Cooper & Condie, 2016). The authors theorize the issues by using Mikhail Bakhtin's concepts on language and dialogue 'to understand how new forms of digital scholarship, particularly blogging and self-publishing' are able to both foster and limit academic dialogues (ibid). One idea throughout the discussion is that of whether digital scholarship represents something 'carnivalesque,' or in other words, something that disrupts traditional, established practices in academia (Bakhtin, 1984b as cited by Cooper & Condie, 2016).

According to the Cooper & Condie (2016), one part of the dominant discourses in academia and research is that these can be viewed as 'finalising' which thus creates a definite, fixed understanding of subjects as opposed to them being viewed as 'unfinalised' and thus changing. Cooper & Condie (ibid) discuss this notion through Bakhtin's view that a more ethical approach to social science is one where research dialogues attempt no finalization of participants in research or topics of inquiry (Frank, 2005 as cited by Cooper & Condie, 2016). Cooper & Condie (ibid) note the example from Bakhtin's analysis of a character called Devushkin from the Dostoevsky novel Poor Folk:

Devushkin, who in recognising himself in another story, did not wish to be represented as ‘something totally quantified, measured, and defined to the last detail: all of you is here, there is nothing more in you, and nothing more to be said about you’ (p. 58). Thus from a Bakhtinian perspective, researchers should not ‘Devushkinise’ their research participants, and the power to finalise people with social science discourses should be scrutinised (Frank, 2005).

In brief, Cooper & Condie (2016) appear to be advocating an 'unfinalised' approach in research that invokes a 'carnivalesque' element is one that seeks to be inclusive by welcoming voices from students, teachers and researchers alike rather than solely established researchers and traditional, established 'norms' within academia.

Traditions in EFL/EAP teaching: the teaching observation

What most interested me about the ideas and theories in the article was the potential applications to teaching within English as a foreign language and English for academic purposes. One tenant of EFL/EAP especially within the UK context is that one should be indoctrinated, as it were, by undertaking the Cambridge CELTA course initially and the Cambridge Delta course subsequently. Indeed, many English language schools and professional organizations, such as BALEAP and the British Council, often require teachers to have one of these qualifications while most UK universities where EFL/EAP is taught often demand the Cambridge Delta qualification which is an expensive and narrowly focused undertaking that does not always fit 'well' within the context of teaching academic writing for university.

Both the Cambridge CELTA and Delta qualifications place a high value on narrow aims for lessons, which must be adhered to in order to demonstrate learning. However, I believe that any experienced teacher would fully understand that a list of 3 aims for the lesson does not indicate learning and will not indicate that the students have learned everything by the end of the lesson. Learning is a continuous process that does not begin and end within the confines of the walls of the classroom. However, those seeking CELTA or Delta qualifications are forced to demonstrate that these fixed aims have been met within the space of 60 minutes, and thus, that learning has been achieved by the students as a result of the teacher's success in addressing and thus ticking off each of the aims!

As part of one's employment as a teacher of English as a foreign language and/or for academic purposes, mandatory observations are often required as part of the contractual obligations, whether employment is in a language school or a university. One set of criteria that observees must note down are the lesson aims. In the observation, the observer will look to these and attempt to identify whether the aims have been met within the context of the lesson plan, often within the space of a 60-90 minute observation.

However, this approach to observations, in my opinion, raises several questions which relate back to the theories in Cooper & Condie's article:

- Can the lesson aims, without a doubt, demonstrate whether learning has taken place after the lesson?

- Do not a series of lesson aims suggest that learning is fixable, and thus able to be finalized?

- Where do student interest and inquiry come into play as far as the lesson aims, and whether these are met or not?

- Where the students and teachers spend more time on specific aims that lead to an aim not being met, should this reflect poorly on the teacher?

A potential solution

I think one potential solution is to revamp how observations are done: they should not be conducted according to how Cambridge CELTA and Delta observed lessons are conducted as these observations are quite narrow in focus and presume that a 60-90 minute 'snapshot' of the teacher is 'enough' to make a value judgement. These observations also tend not to focus on students at all, but solely on the teachers - as if learning and teaching were not a dialogic process! Learning and teaching is a dialogic process - without dialogue, the teacher would become a speaker who talks at the students as opposed to discussing with the students the issues being covered.

Therefore, observations should also look at learning on the part of the students rather than focusing solely on whether the teacher is delivering a lesson and meeting lesson aims according to a plan. A pre-planned lesson on paper might indicate that deviation from the plan should be avoided in order to fulfill the lesson aims and thus the plan. For some reason, lesson aims are traditionally seen as tenants - they must be achieved.

However, learning and teaching in the classroom does not often go according to plan for various reasons. One reason is that students might want to know more about a particular area, and thus might have questions, deep questions, about a particular topic. If we, as teachers, only quickly address their questions on the surface without going into depth in order to meet our aims, I feel we are doing our students a disservice. This also can make teachers appear a bit rushed or hesitant to address students' concerns - within the eyes of the students - at their expense and for achieving the lesson aims, which might negatively affect the atmosphere in the classroom.

Another reason might be that the materials, at times published within a book or within a course pack, might work in theory within the lesson plan and thus within the mind of the teacher but in practice do not work according to plan. In this case, the teacher has to 'teach on their feet' especially they observe that the materials are presenting problems for the students.

Final (but unfinished) thoughts...

To sum up, if learning and teaching is a dialogic process, it is very likely an 'unfinalised' process that does not end once the class has ended. Students do not simply learn everything within the space of 60-120 minutes whether or not lesson aims have been met. Teachers should advocate for different forms of observation in order to reflect the complex reality and nature of learning.

Learning continues through dialogues outside the classroom, whether face-to-face or online through discussion forums or text messaging or most importantly, within the minds of the students. I would argue that learning has no natural endpoint, and thus, it simply cannot be encapsulated or evidenced within a lesson observation.

We can attempt to understand what learning has taken place in the classroom, but in order to do this, observation practices will need to start taking a closer look at the learners perhaps before, during and after a particular lesson. A more 'carnivalesque' approach is merited - one that is inclusive and looks at all participants in the learning and teaching process, and gets a sense of their voices on the processes. A snapshot observation of teachers is old hat, and in the world of the digital - where information can be easily obtained and disseminated to foster and support learning and teaching - I believe such observations are outmoded. A new model for observations must include student learning and participation as they are also key stakeholders in the process of learning and teaching. To close, Bakhtin would not support traditionally accepted notions of teacher observation practices in 21st Century world of teaching English as a foreign language/English for academic purposes, and therefore, change is needed.

Bibliography

Cooper, A., & Condie, J. (2016). Bakhtin, digital scholarship and new publishing practices as carnival. Journal of Applied Social Theory, 1(1). Retrieved from http://socialtheoryapplied.com/journal/jast/article/view/31/7

Are we OK, you and I, after you voted to destroy my dreams? — Andrew Reid Wildman, artist, photographer, writer, teacher

Reflections on the EU referendum result

I came across this moving post which was written as a result of the EU referendum that appears to be causing deep fissures across the UK to surface. Increasing numbers of reports are coming in of xenophobic and racial slurs being hurled against ordinary people going about their daily lives as a result of the slim majority of Britons voting to leave the EU. This is not what the UK stands for, but now that appears to be changing as rightwing extremists celebrate their knife-edge victory.However, no matter how probable or possible, the referendum result is being contested by, as of this post, nearly 3.5 million people who have signed this petition to Parliament which went from around 300,000 signatures on Friday morning after the referendum to nearly 3.5 million as of 22:04 Sunday evening.Personally, I am sincerely disappointed in the result as I view it as a severely backwards step away from cooperation and integration into one that is more isolationist and nostalgic in nature. I personally believe that certain "newspapers" such as The Daily Mail, The Sun and The Express and other related "media" have helped to caused this disastrous result.The "journalists" who work for these papers should be ashamed of themselves... through their actions, by constantly feeding their readers "news" with highly inflammatory headlines and emotionally charged language that have caused people to fear immigration and immigrants, wherever they're from (even the EU) and believe that the UK not only contributes £350 million weekly to the EU, but that this money, following a leave vote, would be put back into the NHS.Perhaps what is disturbing is that readers of these papers took to the highly emotive headlines like puppies to antifreeze: sweet, but deadly. They lapped it all up and made decisions with their hearts rather than their heads.And as a result, the future of those under 25 is suddenly thrown into disarray; they may well not get to benefit from freedom of movement, freedom to work and live in the EU wherever they please. Those under 18 may well not get to enjoy the enormous benefits that the Erasmus Programme creates: studying abroad in the EU, developing an intimate understanding of another culture, language and people - all of which break down barriers and help peoples to understand better one another... The list goes on, let alone Scotland now positioning itself to leave.Who knows what will happen...

I came across this moving post which was written as a result of the EU referendum that appears to be causing deep fissures across the UK to surface. Increasing numbers of reports are coming in of xenophobic and racial slurs being hurled against ordinary people going about their daily lives as a result of the slim majority of Britons voting to leave the EU. This is not what the UK stands for, but now that appears to be changing as rightwing extremists celebrate their knife-edge victory.However, no matter how probable or possible, the referendum result is being contested by, as of this post, nearly 3.5 million people who have signed this petition to Parliament which went from around 300,000 signatures on Friday morning after the referendum to nearly 3.5 million as of 22:04 Sunday evening.Personally, I am sincerely disappointed in the result as I view it as a severely backwards step away from cooperation and integration into one that is more isolationist and nostalgic in nature. I personally believe that certain "newspapers" such as The Daily Mail, The Sun and The Express and other related "media" have helped to caused this disastrous result.The "journalists" who work for these papers should be ashamed of themselves... through their actions, by constantly feeding their readers "news" with highly inflammatory headlines and emotionally charged language that have caused people to fear immigration and immigrants, wherever they're from (even the EU) and believe that the UK not only contributes £350 million weekly to the EU, but that this money, following a leave vote, would be put back into the NHS.Perhaps what is disturbing is that readers of these papers took to the highly emotive headlines like puppies to antifreeze: sweet, but deadly. They lapped it all up and made decisions with their hearts rather than their heads.And as a result, the future of those under 25 is suddenly thrown into disarray; they may well not get to benefit from freedom of movement, freedom to work and live in the EU wherever they please. Those under 18 may well not get to enjoy the enormous benefits that the Erasmus Programme creates: studying abroad in the EU, developing an intimate understanding of another culture, language and people - all of which break down barriers and help peoples to understand better one another... The list goes on, let alone Scotland now positioning itself to leave.Who knows what will happen... Anyway, do have a read of the post below, it is moving...

Anyway, do have a read of the post below, it is moving...

I feel like someone has taken something dear to me, my identity, my connection to my continent, and they have killed it. If you voted Leave, I hope you are prepared to take responsibility for what you have done, and that you do not regret it. It is over to you now, to sort out. […]